Visit the Reflect: Art and History Gallery hosted by UHS Survivor Services and Violence Prevention in recognition of Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM).

The art and history gallery spotlights significant historical events related to campus sexual assault activism over the last 50 years alongside art by student survivors.

View an online version of the exhibit below.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Content Warning

This exhibit contains depictions of gender-based violence, discrimination, and sexual assault. We acknowledge that this content may be activating for survivors and we encourage you to do what you need to take care of yourself. Confidential support, counseling, and resources are always available to you at no cost through University Health Services.

April 1–30, 2025

10am–8pm Daily

Student Activity Center

4th Floor, 333 East Campus Mall

Passage of Title IX

1972

Title IX Passes

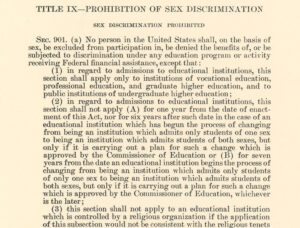

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

– The first 37 words of Title IX

About Title IX

On June 23, President Nixon signed Title IX into law as part of the Education Amendment Act of 1972. Although Title IX eventually gained notoriety as a law mandating equal funding, access, and facilities in public sports–and became interchangeable with campus sexual assault–its origin stories stemmed from cases of faculty employment discrimination in academia.

Title IX is designed to protect individuals from discrimination based on sex in educational institutions that receive federal financial assistance. While Title IX is celebrated (and debated) today, it passed with little fanfare or national attention in 1972. At the time, the Education Amendments were far more controversial for its inclusion of anti-busing and segregation measures.

Who helped create Title IX?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Bernice "Bunny" Sandler

In 1969, Bernice “Bunny” Sandler was a soon-to-be doctoral graduate of the University of Maryland, who was job hunting for a postdoctoral or faculty position. After receiving the feedback “you come on too strong for a woman,” she began to research gender discrimination law. Upon discovering the existence of a 1968 Executive Order that prohibited sex discrimination by federal contractors (and making the connection that colleges receive federal contracts), Sandler used her this knowledge to file complaints against hundreds of campuses and mail letters to members of Congress, one of which caught the attention of Edith Green.

Edith Green

Representative Edith Green (D-OR), the “mother of Title IX,” was instrumental in leading the 1970 hearings that became the legislative foundation for Title IX. At the time of the hearings, there were just 11 women in Congress. All 15 members of the House Special Subcommittee on Education overseeing the hearings were men—seven of whom did not bother to attend the hearings. At the time, the most controversial point debated in the hearings was whether sex discrimination was a bigger problem in academia than race discrimination. Putting the plights of marginalized groups in competition with each other is still a commonly used political tactic of oppression used today.

Patsy T. Mink

Representative Patsy T. Mink (D-HI), often honored as the author of Title IX, was also the first woman of color and Asian-American ever elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Inspired by her own experiences of gender discrimination in her pursuit of a medical degree, Mink remained a fierce and lifelong advocate for equal opportunity in education for her entire career.

“Millions of women pay taxes into the federal treasury and we collectively resent that these funds should be used for the support of institutions to which we are denied equal access.” – Patsy T. Mink

Pushback and New Precedents

1980s

Challenges to Title IX

Dozens of court cases and congressional bills attempted to challenge Title IX. These challenges strengthened the legal precedent for Title IX protections.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

1980: Alexander v. Yale

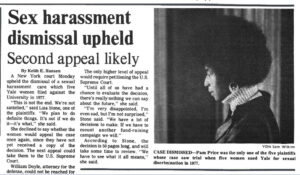

This was the first case to demonstrate that Title IX protections apply to sexual harassment. The case was originally named for Ronni Alexander—a Yale sophomore who reported being raped by the university’s band leader, who had been accused of rape and sexual harassment by other students. Pamela Price was asked to join the case with Alexander and three other complainants to establish a pattern of unchecked sexual harassment at Yale. Price reported being sexually propositioned by a professor who proposed he would give her an A in exchange for sex. She refused and the professor graded her a C. Price filed a written complaint with a university dean. At the time, there was no established grievance procedure, and nothing came of Price’s complaint.

A district court affirmed that Title IX could indeed apply to sexual harassment but dismissed the four other parties on technicalities. The case proceeded with Price as the lone plaintiff. For Price and many watching, it felt like a decision pitting a Black woman student against a white male professor and white institution.

Price lost the trial and appeal, but the precedent sent a chilling warning to universities around the country. Soon, many major universities, including the UW-Madison, adopted formal sex discrimination policies and grievance procedures.

1983: Mullins v. Pine Manor

Decided in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, Mullins v. Pine Manor clarified campuses’ role in protecting student safety. In 1977, student Lisa Mullins was abducted from her campus dorm room, dragged across campus with a pillowcase over her head, and raped in the campus dining hall. Mullins brought charges against the university, arguing that both the campus requirement to live in university housing and the faulty security measures in place made them liable for the attack. The university argued that they had no duty to protect its students against criminal acts of third parties. The court sided with Mullins and the case captured public attention, laying the groundwork for legislation on campus safety that defines college life today.

1984: Grove City College v. Bell

In 1976, the president of Grove City College, a private, Christian college, refused to participate in the Department of Education’s assurance of compliance procedures for Title IX regulations. Grove City argued that, because they did not receive federal funding, a key parameter of Title IX, they did not need to comply with the law. The Supreme Court clarified that, even if a university itself does not receive government assistance, the flow of financial aid from the Department of Education through student loans does constitute federal funding and that the college either needed to comply or stop accepting federal student loans.

Laying the Legal Precedent

1990s

Clery Act and other key legislation

Today, expectations for American universities to prevent and respond to campus sexual violence are largely shaped by the legislative relationship between the Title IX, the Clery Act, and VAWA.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

1990: Clery Act

Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act (known as the Clery Act) was passed by Congress in 1990. The Clery Act requires colleges and universities to keep and disclose up-to-date logs of crimes that take place on campus property. The statute was named to honor Jeanne Clery, a student at Lehigh University who was raped and murdered in her dorm by another student in 1986. Jeanne’s parents were convinced that the university could and should have done more to prevent this tragedy and became tireless advocates for change, influencing the eventual passage of the law.

Today, college students receive timely crime warnings and the Annual Security and Fire Safety Report that share information about campus crimes—both are legacy of the Clery Act.

1992: Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools

Christine Franklin was a high school student at North Gwinnett High School in Georgia who was the target of ongoing sexual harassment and abuse from Andrew Hill, a coach and educator employed in her school district. The school administration was made aware of the behavior, did nothing, and discouraged Franklin from pursuing charges. Franklin sued the school district for personal injury, demonstrating years of sexually explicit comments, forced kissing, and coerced intercourse on school grounds from the teacher. For the first time, the Supreme Court ruled that monetary damages are available under Title IX. The court’s decision was unanimous. Previously, the only justice available was the hope that the Department of Education Office of Civil Rights would complete an investigation, determine that the school violated Title IX, and issue a citation requesting they do better.

1994: Violence Against Women Act

Democratic House representatives introduced the Violence Against Women Act in 1991 (VAWA). VAWA was signed into law by President Clinton, and was the largest federal effort to address gender-based violence. VAWA established the first national domestic violence hotline and changed law enforcement policies for arresting and prosecuting domestic violence offenders. In a 2012 report, the U.S. Department of Justice estimated that national rates of intimate partner violence fell 64 percent between VAWA’s passage and 2010.

Today, expectations for American universities to prevent and respond to campus sexual violence are largely shaped by the legislative relationship between the Title IX, the Clery Act, and VAWA.

Survivor Activism at UW-Madison

2008

Laura Dunn graduates

A survivor advocate at UW-Madison, Laura Dunn shaped both local and national legislation.

“It was late, I wanted to be safe. I had no reason not to trust them. I thought rape was a stranger jumping out of an alley attacking you with a knife. I didn’t have any narrative where it’s someone I knew.”

-Laura Dunn, interview for People Magazine in 2017

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Laura's Story

Laura Dunn, a UW-Madison student athlete, was sexually assaulted while incapacitated from alcohol during her freshman year by members of the men’s rowing team who walked her home. Dunn reported the assault to the Dean of Students Office and the UW Police Department one year later, by which point one of the assailants had graduated. The university concluded its investigation the following year, finding the men not responsible; the District Attorney’s office also declined to press charges. At the time, Wisconsin law did not consider alcohol a legal intoxicant capable of altering the ability to consent in rape cases.

Common for sexual assault survivors, Dunn managed safety measures and retaliation on her own. She dropped her sport to avoid seeing the attacker who remained on campus and cut ties with mutual friends who did not want to get involved. Dissatisfied by how the university handled her disclosure and case, she became one of the first students to file a Title IX complaint against a large, public university. In 2008, after Dunn graduated, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) ruled in UW-Madison’s favor and found that the university was not responsible for violating Dunn’s Title IX rights.

Motivated by the injustice she faced, Laura earned a law degree and became involved with federal campus sexual assault legislation. She served on the 2014 rule-making committee to shape the regulations of the Campus SaVE Act.

Clarification in Congress

2010s

Clarification in Congress

“The sexual harassment of students, including sexual violence, interferes with students’ right to receive an education free from discrimination…” – From the 2011 Dear Colleague Letter

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

2011-2016: Dear Colleague Letters

In 2011, under the Obama administration, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) released an important “Dear Colleague Letter” to Congress, which included important guidance on Title IX. The letter clarified that sexual violence—including sexual assault, rape, and sexual coercion—is not only a crime, but constitutes discrimination. The letter and subsequent guidance explicitly outlined universities’ obligations to both respond to and take meaningful steps to prevent sexual harassment and violence. This put universities on official notice that the Office of Civil Rights would pay closer attention to how schools’ handle sexual assault cases and established that the preponderance of the evidence standard (i.e., it is more likely than not that sexual harassment or violence occurred) is most appropriate for investigating allegations.

Over the next five years, the OCR issued more Dear Colleague letters providing guidance on students’ civil rights related to gender discrimination, including rights of pregnant (2013) and transgender students (2016).

2013: Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act (Campus SaVE Act)

As part of the VAWA Reauthorization Act of 2013, the Clery Act was amended with a series of changes referred to as the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act (Campus SaVE Act). The Campus SaVE Act expanded Clery reporting and transparency requirements to include disclosing statistics on dating violence, domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking. It expanded victim rights, accommodations, and protective measures to survivors, regardless of whether they choose to report to law enforcement. Colleges also became required to provide education and awareness programs to its students, which is why most campuses to this now require some sort of sexual violence education program during orientation.

Activism and Attention

2010s

A movement decades in the making

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

2012: Andrea Pino and Annie Clark

Andrea Pino and Annie Clark, were two student survivors attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. While the sexual assaults they experienced were very different—Clark was attacked by a stranger and Pino raped in a bathroom at an off-campus party—their shared experience of being dismissed and discouraged by the university upon

reporting was similar. The women learned everything they could about campus sexual assault legislation on their own and filed a 34-page complaint to OCR against UNC. They traveled the country assisting other student survivors in filing suits, marking their progress on a map of the U.S. When the Department of Education released the list of 55 universities under Title IX investigation, the list nearly matched Pino’s and Clark’s map. Their cases and advocacy work brought national attention, including the front page of the New York Times.

2013: Know Your IX

Frustrated and motivated by how they each had to piece information about rights and resources together for their own sexual assault

cases, Amherst College student Dana Bolger and Yale Law School student Alexandra Brodsky created the Know Your IX website. What was initially thought of as a short-term project to host crowd-sourced resources for legal action, campus organizing, and self-care blossomed into a comprehensive web resource for students across the country seeking information about complaint filing procedures and statutory requirements.

2013-2014: National Attention

Campus sexual assault became a matter of public discourse outside of higher education circles. Time magazine, the New York Times, and Rolling Stone all ran cover stories on the topic between 2013 and 2014. The Rolling Stone story was later retracted for faulty reporting.

“The truth is, for young women, particularly those who are 18 or 19 years old, just beginning their college experience, America’s campuses are hazardous places.” – Eliza Gray, TIME May 2014

2014: Emma Sulkowicz’s “Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight)”

In 2014, Columbia University art student Emma Sulkowicz made national news with their endurance art piece titled, “Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight).” The senior thesis performance involved Sulkowicz carrying a 50-pound mattress across campus to represent the dorm bed they reported they were raped on. Sulkowicz vowed to carry the mattress until the named attacker was expelled or graduation, whichever came first. The accused party was found not responsible, and Sulkowicz carried their mattress, assisted by fellow students, across the graduation stage. In solidarity with Sulkowicz’s cause, many mattress-carrying protests took place at other campuses.

2015: The Hunting Ground

In 2015, the documentary film The Hunting Ground premiered and highlighted the problem of campus sexual assault and systematic failures of college administrations to address the issue.

Kamilah Willingham, a survivor activist featured in the film, reported that she and a friend had been sexually assaulted by a fellow Harvard University student in 2011. An independent attorney hired by Harvard to conduct the investigation initially found the case credible, and recommended expulsion. When the accused student appealed, a panel of Harvard Law faculty overturned the original findings, using a standard of evidence that would eventually be considered a violation of Title IX. Willingham faced public backlash from her alma mater after appearing in The Hunting Ground. A group of 19 Harvard professors issued a press release and penned an open letter disputing Willingham’s claim and offering support for her assailant.

The Hunting Ground was met with critical acclaim and was nominated for an Academy Award and won an Emmy.

UW-Madison's History

1990s-Today

Sexual violence prevention on campus

Between prevention, advocacy, research, and Title IX compliance, UW-Madison employs dozens of full-time staff dedicated to sexual violence prevention in 2024.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

1990s

University Health Services hired its first prevention coordinator to work on issues of campus-based violence.

2001

UW-Madison student Angela Rose forms PAVE (Promoting Awareness, Student Empowerment). Today, PAVE is a national organization with chapters all around the country. At UW-Madison, PAVE maintains an operational budget of around $80,000.

2007

University Health Services is awarded a Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) grant to expand efforts to coordinate campus-based services.

2008

Laura Dunn graduates and the Office of Civil Rights finds UW-Madison not responsible for violating her Title IX rights.

2010

UW-Madison conducts its first comprehensive student needs assessment identifying dating violence survivors as an underserved population.

2013

In anticipation of new regulatory guidance, UW-Madison begins requiring interpersonal violence education for first-year students rather than encouraging it. Similar requirements for graduate students and employees follow soon after.

2014

The Violence Prevention and Survivor Services office expands from one to three full-time staff.

2015

The first AAU Campus Climate Survey is administered to UW-Madison students, with results released in the following year. Among other key findings, the survey revealed that more than one in four undergraduate women reported experiencing sexual assault during their time on campus. The survey also found concerning rates of sexual harassment reported by graduate student from faculty, staff, and administrators.

2016

UW-Madison hires its first full-time Title IX Coordinator. Three additional full-time positions are added to Violence Prevention and Survivor Services, totaling a team of seven.

2022

Sexual violence prevention and response was identified as one of the eight strategic key initiatives within the Student Affairs strategic plan. This initiative aims to create and support cross-campus systems for coordinated sexual assault response with a focus on prevention, increasing access to care and building a trauma informed campus.

2024

The Sexual Assault Prevention and Community Equity Toolkit (SPACE Toolkit) taskforce was created.

Audio Stories from Our Campus Community

Coalition Building

Listen to ASM’s Anti-Violence Chair Landis Varughese speak about the role that was created to serve as a liaison between students and campus decision-makers around sexual violence prevention.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Transcript - Landis Verughese

Hello, my name is Landis Varughese, I use he/him pronouns and I serve as the anti-violence coordinator for the Associated Students of Madison: UW-Madison’s student government. In my role as AVC, I primarily serve as a liaison between students and campus partners surrounding restorative security measures for our campus. Although I am the second person to ever hold this role, I have learned so much about the importance of activism when it comes to prevention sexual violence on college campuses.

I’ve found that coalition building is paramount to any future in which campus sexual violence’s impact is nullified. When you are working alongside like minded individuals, who are just as passionate about creating the change that you wish to see in the world as you are — anything is truly possible. For me, helping lead the Student Title IX Advisory Board (STIXA) has been one of the most rewarding experiences in my time on UW-Madison’s campus. Working with fifteen students who are emboldened to create change to the culture that enables sexual violence and raise awareness of the Title IX regulations and procedures for students in need of navigating this process. Understanding that these relationships we build with other student leaders are truly unique in the sense that we share a common objective or objectives. We learn from each other, build each other up, and support each other in our collective efforts. We celebrate our victories, sit with our losses, but more importantly continue to fight the good fight because that will take us into a future where sexual violence is no longer an issue facing college campuses.

I’m forever grateful to be in the position that I am in, to be in close proximity to key decision makers and professionals, while also being in community with students. The nature of my role necessitates that I work with folks from all over campus to relinquish the power that violence has had, and this is something that I don’t take lightly. It’s also important for me to note that the work is not easy, and the losses column can fill up quite quickly — but the very nature of this work and the people I work with is the greatest victory for me. Having allies from different walks of life, and roles and responsibilities on this campus inspires me continue to push the envelope in campus sexual violence activism. It takes a village, or rather an entire campus, to push back against campus sexual violence, and I cannot wait to see this kind of coalition and community building continue to flourish until we never have to worry about this problem again.

Student Activism

Listen to former PAVE Chair Eli Tsarovsky discuss the importance of activism and community care.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Transcript - Eli Tsarovsky

Hi! My name is Eli Tsarovsky. I was the Chair of PAVE-UW in 2021 and have been a student activist on campus in various capacities. As an activist working in sexual violence prevention, it was important to ground myself in the story and solutions created by survivors and be intentional by creating a truthful narrative of the data campus to compel institutional action while furthering our student-led movement. Being a part of activism on campus for issues that are close to you can be daunting. The moral and best next step can be hard especially when it involves money and robust institutional response. What is grounding as a student activist is the people and community of students.

When you are in a movement against violence on campus, it is important to ground yourself in collective power of the people. We talked of our actions as a movement because it involved everyone in our community and not just about individual change but cultural change. Our messaging centered care and support because we believed in the hearts and minds of all of people on campus to do better and we aimed to show what community care looked like. We advocated our shared message of supporting survivors and ending violence through peer education, collaborative events, social media, student journalism, and marching in the streets of campus. We knew our community needed to learn the true facts about violence on campus and hear different ways of approaching community solutions by honoring the great Black, Brown, and indigenous scholars and activists through our education and events. We grounded our education and events in an Anti-Violence Framework that honored and was grounded in Black Abolitionist Feminism. We provided people ways to learn about all sides of violence from supporting survivors, educating others, and bystander intervention, to the legal landscape. Education was power and with the power of our community we acted.

Continued Learning

Listen to Prisma Ruacho from the Multicultural Student Center reflect on how continued learning around sexual violence has inspired her work.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Transcript - Prisma Ruacho

Strategic Initiatives

Listen to Molly Caradonna, Director of UHS Survivor Services, talk about current and future strategic initiatives to prevent sexual assault on campus.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Transcript - Molly Caradonna

Hello. My name is Molly Caradonna, I use she/her pronouns, and I am the Director of UHS Survivor Services. In my role, I support the integrated care team of survivor advocates, mental health providers and medical professionals that provide the no cost, confidential services available at Survivor Services. Another aspect of my role is supporting the broader, cross-campus work happening to end sexual violence on our campus and improve the services available to our student survivors.

I’m really energized about the commitment to sexual violence prevention and response as a key priority in the newly adopted Student Affairs strategic plan.

Since fall 2022, I’ve been working with a core team of campus leaders across Student Affairs to strategically and proactively address the current state of sexual violence on our campus. We’ve set goals to create and support cross-campus systems for coordinated sexual assault response, with a focus on prevention, increasing access to care, and a trauma-informed campus.

So, what concrete actions is the University taking as part of this strategic plan?

First, we’ve collaborated with the primary researchers of the SHIFT study at Columbia University (Drs. Jennifer Hirsch and Shamus Khan) who completed the most comprehensive study on campus sexual assault to date.

The research for their 2020 book Sexual Citizens guided the creation of Sexual Assault Prevention and Community Equity, or SPACE, toolkit that guides campuses in developing their violence prevention strategies. In 2024, UW-Madison plans to use the SPACE toolkit to investigate the ways that the built university environment and the inherent power and equity dynamics underlying these spaces, contribute to or mitigate the risk of sexual violence on our campus. More specifically, this toolkit asks campus to consider power/equity across various types of space on-campus, including: residential spaces, social spaces, virtual spaces, programmatic spaces, and public spaces.

Our SPACE Toolkit task force consists of nearly equal staff and student members with representation from Fraternity & Sorority Life, Campus Event Services, University Housing, Dean of Students Office, University Health Services, the Libraries, Cross-College Advising Services, Athletics, University Veterans Services, and Transportation. Together, over the next year, the SPACE Toolkit task force will audit the campus and make concrete recommendations for adaptations to our campus space and the policies/procedures governing those spaces, in order to reduce the risk of sexual violence.

The second key goal of our strategic plan on sexual violence involves improving the cross-campus response to sexual violence. In early 2024, Dr. Lori Reesor, UW-Madison’s Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, endorsed the creation of two standing university committees. First, a “Gender-Based Violence Prevention & Response Coordinating Committee” charged with building the internal capacity and infrastructure of coordinating offices to effectively address campus sexual violence through training, professional development, interdisciplinary collaboration, research-to-practice facilitation, and advising.

The second recommended group is a UW-Madison sexual assault response team (or SART) charged with coordination between offices that respond to sexual misconduct and work directly with impacted students, in order to enhance collaboration with organizations inside and outside the University, ensure trauma-informed response, and improve accountability and/or transformative justice mechanisms.

While much work remains to be done, I continue to be personally moved and inspired to act, based on the stories and activism of our student survivors. I am hopeful about the concrete solutions and advancements that will come from the work of our Student Affairs core team. I also ask that each of you reflect upon your individual contributions to our campus climate, considering your role in contributing to our collective responsibility for creating a campus that is safe and equitable for all of our students.

Student Organizations

Listen to PAVE peer facilitator Spencer Runde discuss PAVE’s history and current work on campus.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Script - Spencer Runde

When looking back on the history of student activism on campus, specifically for the prevention of sexual assault, it is vital that we recognize the PAVE organization. PAVE stands for Promoting Awareness Victim Empowerment, and our mission is to prevent sexual assault, dating violence, stalking, and more through education and activism. We accomplish this by hosting volunteer groups, orchestrating workshops for other orgs and events on campus, and different awareness-raising campaigns throughout the years. PAVE was originally founded in 2001 by UW student Angela Rose, forming a group that uses education and action to deconstruct rape culture and address forms of sexual and power-based violence. Nowadays, PAVE has chapters in other countries all over the world reaching places such as Australia and India. Angela Rose is still the head of the national organization.

Angela Rose and other campus advocates against sexual violence have helped mold PAVE into what the organization is today; a confidential, peer-led resource for students seeking education or support regarding power-based violence. Our office, located in the Student Activity Center, is a large room designed to provide a comforting atmosphere for students and staff alike. Some events hosted regularly in the office are our Support Spaces, our Volunteer Leadership Program (VLP), and our Peer Education Program (PEP). Support Spaces are a weekly event that provide a chill atmosphere that allows students to come into the office and seek support from our confidential peer staff or just hang out and do homework. VLP is one of our volunteer programs that meets once a week and focuses on a project that spreads PAVE’s message throughout the year. As for our other volunteer program, PEP, it focuses on educating our volunteers on some of our workshops and teaching them to facilitate. This program also assists volunteers in actively engaging with important conversations surrounding these taboo topics with family, peers, and relationships in their lives. These volunteer groups are our main way of addressing power-based violence and strengthening prevention on this campus.

PAVE has a primary focus on planning and executing several events during the month of April, which is also known as Sexual Assault Awareness Month or SAAM. These events can range from anything involving DIY arts & crafts and documentary showings to panel discussions with professionals in the field of violence prevention. PAVE is dedicated to providing resources for survivors while engaging in sexual violence prevention, especially during this month.

At PAVE, the knowledge our organization carries is constantly evolving and spreading. Something we like to say at the office or in one of our workshops is, “What is said here, stays here, but what is learned here, leaves here.”

Community Resources

Listen to Morgan Reed, a Youth Violence Prevention Advocate at DAIS (Domestic Abuse Intervention Services), talk about the resources and support DAIS can provide for UW–Madison students and others in the community.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Transcript - Morgan Reed

Hi! My name is Morgan Reed, and I use she/her pronouns. I’m a Youth Violence Prevention Advocate at Domestic Abuse Intervention Services, or DAIS, located on the north side of Madison. For almost 50 years, DAIS has worked to empower those affected by domestic violence through support, education, and outreach. The outreach piece is what brings me to you in this Reflection series for Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Thank you for tuning in!

DAIS is dedicated to making Dane County a safer place for people impacted by domestic violence. We offer a wide range of crisis intervention and prevention programs, including legal advocacy, support groups, and emergency safety planning. We also operate the only homicide prevention shelter in Dane County. No matter what, we’re always available through our 24-hour Help Line and text line.

My work with DAIS focuses on preventing intimate partner violence and fostering community awareness. We provide tailored training on intimate partner violence for a variety of groups—business professionals, UW medical students, Girl Scout troops, and more.

So why am I, an advocate from DAIS, speaking to you at UW-Madison? Because DAIS is a resource for you—before, during, and after college.

Let me illustrate this by telling you about Haley. Though she’s not a real person, her story reflects the experiences of those we work with at DAIS. Content warning for sexual violence and emotional abuse.

Haley grew up in Madison and first encountered DAIS in high school during a health class presentation about teen dating violence. She also had a friend involved in MENS Club—or Men Encouraging Nonviolent Strength—a DAIS primary prevention program where male-identified youth discuss gender-based violence and how to be allies.

At UW-Madison, Haley occasionally saw DAIS tabling at events like “Coffee and Consent,” learning that DAIS, like UHS, was a resource for students. But it wasn’t until her junior year that Haley truly considered reaching out.

At that point, Haley’s boyfriend had grown possessive—getting jealous when she went out with friends, demanding her location, and manipulating her trust. More than once, Haley felt pressured into sex. Though uneasy, she blamed herself. It took her friend Brianna expressing concern and reminding her about DAIS for Haley to seek help. Together, they nervously called the Help Line.

It took Haley a year to leave the relationship, but DAIS supported her every step of the way. They helped her create a safety plan for senior year and provided a tech clinic appointment to check if her ex was tracking her phone. Even after graduation, Haley used the DAIS text line for emotional support.

Haley’s story is just one of many. Sexual violence and intimate partner violence remain prevalent during the college years. But support from DAIS isn’t limited to your time as a student. Our FREE and confidential services are available to anyone in Dane County. So, whether you’re lying awake at night reflecting on this series or currently feeling trapped in a relationship, DAIS is here for you.

Wherever you are, whatever you do, remember: you are surrounded by survivors. But also remember, DAIS is a resource for you—always.

Looking Ahead

2024 and Beyond

Future Direction

What comes next?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Long-lasting Legacy

After 50 years, Title IX has changed the landscape of the American education system, athletics, and civil rights. What was originally conceived as an employment discrimination law later became known to the public as a gender parity in sports law, then a campus sexual assault law. Since its implementation in the 1970s, women’s participation in high school sports has grown from fewer than 300,000 to more than 3.5 million students.

Today, the specifics of Title IX regulations fluctuate with each presidential administration, including guidance around regulations concerning transgender and pregnant students.

Unfinished Business

History has often witnessed legislation dividing identity groups, often out of political strategy to advance change. In fact, Rep. Edith’s Green’s first draft of Title IX borrowed language directly from Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, replacing “race” with “sex,” not adding to it.

This strategy means that students who face discrimination based on multiple, intersecting identities are left to navigate several offices and varying procedures. Creating greater cohesion in civil rights across protected statuses like sex, gender, orientation, race, color, national origin, and ability has the potential to expand education protections for all students.

Title IX at UW–Madison

Even as regulations change and evolve, UW–Madison is looking to the future of sexual violence prevention and response.

In 2024, two campus groups were convened to address gaps in campus coordination: a sexual assault response team and a community of practice. Having listened to survivors on unsatisfying outcomes and a failure to meet their needs through formal justice and conduct procedures, campus decision-makers are exploring restorative/transformative justice options available to student survivors.