Think about when you are hungry: You may feel light-headed, sluggish, or have difficulty focusing. What would it be like to feel hunger and have to attend class, work part-time, and study for an exam? For some students, affording and accessing food is a challenge that can contribute to anxiety, isolation, and adverse academic consequences. A student-led campus push to bring access to food to the forefront is driving awareness of campus and local resources for students who may not have enough to eat.

The 2016 national study “Hunger on Campus” estimated that 20 percent of students at four-year institutions are food insecure, which means they lack reliable access to sufficient quantities of affordable, nutritious food. That number nearly triples among students of color and first-generation college students. Seventeen percent of the UW–Madison class of 2020 are first-generation students. At its core, food insecurity is a financial issue, but it also has the power to undermine academic success and impact other facets of student life.

Lydia Zepeda, a UW–Madison professor of Consumer Science whose research focuses on food production, food consumption, and access to food, conducted a local study titled “Hiding Hunger” to find out why people who qualify for food banks choose not to use them. The study’s participants included undergraduate and graduate students as well as community members. Zepeda received interest from more student participants than the study’s funding could accommodate and while there is no data to show the exact number of food insecure students at UW-Madison, she believes it is higher than what is perceived.

Many of the students’ participants in “Hiding Hunger” indicated that their involvement in Zepeda’s study was the first time they shared their feelings about being food insecure, and how not having money for food meant that they could not socialize with their friends.

“Students in the study indicated they were very socially isolated. They couldn’t share that they were struggling because they felt shame,” says Zepeda.

Molly Kloehn, was a mental health care manager at University Health Services and regularly interacted with students who were struggling with food and financial insecurity.

“Food insecurity is very present on campus but under-reported because it’s something that students might not feel comfortable disclosing to peers or campus officials.”

Responses to Zepeda’s study indicated that some students were not eating, or not eating an adequate amount, which could exacerbate conditions of stress, anxiety, and other non-physical health issues.

“Even if they’re not hungry and eating food that’s not healthy for them—crackers, macaroni—they’re not going to be able to perform their best and are going to have other physical and possible mental health problems,” says Zepeda.

“The daily impact of food insecurity on a student is significant,” says Kloehn. “A student may come in seeking mental health services, or they were recommended to come to UHS because of other concerns. When they get here, they say ‘The problem is that I don’t have enough to eat. How am I supposed to focus on my studies or my mental health if I don’t have adequate nutrition?’ The worry and the stress related to finances and nutrition can overshadow the student’s reason for being at UW–Madison. It is a huge barrier to success.”

During the intake process for new clients at UHS Mental Health Services, Kloehn says students are specifically asked if they have ever had a time where they have been concerned about their ability to pay for rent or not had enough food to eat. “It it’s an optional question so clients can decline to answer it, but I’ve seen a lot of ‘yes’ responses in regard to not having enough food to eat.”

Kloehn says one resource that has provided immediate relief to students is BadgerFare, $25 meal cards that can be used at Union dining halls. There is no application to fill out and the gift card amount does not need to be repaid.

“That extra $25 assistance is such a relief. I can see that in their faces. I gave a few out last week and I told the students to treat themselves. Enjoy it, give yourself a chance to have a good meal.”

Students helping students

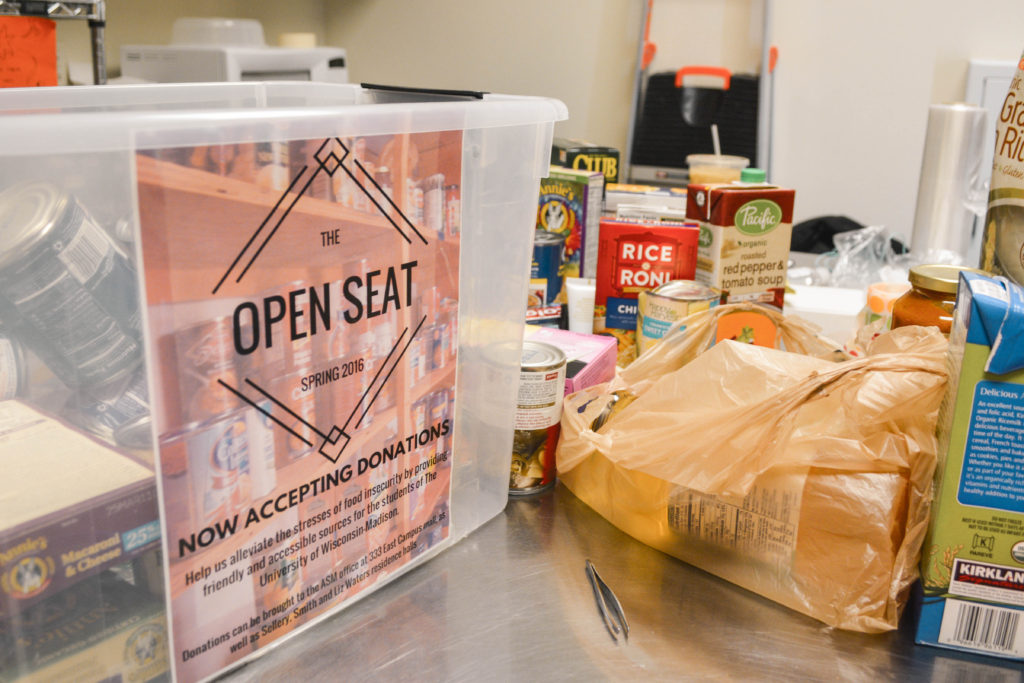

“Hunger on Campus,” the national study, showed that the number of food pantries on college campuses quintupled in the last five years, from 35 to 184. In 2016, UW-Madison’s first student-focused food pantry—The Open Seat—was formed by Associated Students of Madison. The Open Seat served 157 students in 2016-2017 academic year with 67 students visiting for the first time during the fall semester.

Samantha Arriozola, a senior majoring in English and creative writing, is a member of The Open Seat and says the organization’s mission is to ensure that every UW-Madison student is able to go to class, take exams, and excel as students without an empty stomach or fear that they will be unable to secure food.

“We have worked diligently to ensure that students do not feel that there’s a specific level of need which must be met in order to come to The Open Seat. We do not ask for anyone’s economic status or if they receive financial aid as a requirement,” says Arriozola.

The Open Seat is available to students three days per week and by appointment. All items at the food bank are assigned a point value and students receive 30 points weekly. Unused points are not eligible to be carried over to the following week. There are 19 donation sites across campus, including at College Library, the Student Activity Center, and the Natatorium.

“We are student-run, for students. Whether you are a graduate, undergraduate, transfer, international, or any other categorized student, you are welcome at The Open Seat.”

In addition to The Open Seat, there are a number of student organizations focused on mitigating food insecurity that have harnessed resources under the umbrella of the Student Food and Finance Coalition. Marah Zinnen, a senior studying dietetics and global health, is involved in two registered student organizations: The Campus Kitchens Project and Slow Food UW. “My experience working on campus food insecurity is that it’s a more significant issue than we think.”

Zinnen and other students within the Student Food and Finance Coalition knew multiple resources existed but they were not in a centralized location making it easy for students to access. Partnering with University Health Services, the Student Food & Finance coalition developed a comprehensive list of free, easy-to-access campus and community resources online for students.

In October, the Flamingo Run store inside Gordon Dining & Event Center became the first location on campus to accept the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—more commonly known as food stamps— as payment for federally eligible grocery items. Associated Students of Madison unanimously voted to approve this the use of SNAP on campus in March 2017. University Housing, which operates campus dining facilities, hopes to expand SNAP to other on-campus stores in the future.

The biggest challenge for student organizations focused on food insecurity, Zinnen says, is how to advertise their resources without further stigmatizing students.

“The food movement can be exclusive and we recognize that within our community, there are areas that don’t have access to good, clean, fair food. We don’t use the words ‘hunger’ or ‘food insecurity’ in our promotion efforts or on social media,” says Zinnen. “We have the food, we have the space but how do we get students to come forward? If someone is hungry, you’re not going to notice. You’re not going to see it.”

Each week, Slow Food UW—which has served 2,000 individual meals since spring 2015—feeds 400 students through their family dinner night and community meals. Students can purchase discounted meal tickets online ahead of time or indicate when they arrive that they would like to use a ‘pay it forward’, free meal funded by donations from other student diners. Zinnen says the discounted meal tickets regularly sell out but only two pay it forward meals have ever been requested in person.

Identifying Hunger

According to the Office of Student Financial Aid, 61 percent of incoming students have applied for federal financial aid. The students who participated in “Hiding Hunger” attributed their food insecurity to being responsible for their expenses, parental unemployment, or they no longer wanted to ask their parents for money.

In addition to supporting themselves here in Madison, Kloehn is aware of many students who send money to their families. “It can be very stressful for students to focus on academics while thinking about their own basic needs and the needs of their family.”

“Students who need help accessing food may not always ask for it. Food is often what gives because it’s the component they have control over,” says Zepeda, who adds that a key reason why students avoid food pantries is due to a lack of understanding of how they function. “Students in this study identified as middle class. Their families never used food pantries or the students didn’t think they qualified. They felt that by using a food pantry, they would take away from people who needed it.”

Zepeda describes the students who participated in her study as high achievers. “These are the kind of students you want in your classes because education is so important to them. They were making sacrifices to build their future.”

“We have really resilient students on this campus. It’s stunning what students will do to support themselves and their families, sometimes against the odds,” says Kloehn. “There are incredibly resilient students with a lot on their shoulders and anything we can do lift them up is the right thing to do.”

written by Kelsey Anderson, UHS Marketing & Health Communications